Himarë, Dhërmi

Himarë is a resort town on the Albanian Riviera. The local population is predominantly Greek, being Christian Orthodox and speaking both Greek and Albanian. They even have their own Himariote dialect, which is unexpectedly classified as a Southern Greek dialect.

For some reason this small town is very popular among Australians and Kiwis. I wanted to uncover this mystery and asked a lot of them the same question: “Is Albania famous for its beaches?”. I would think that it’s not, but I received mostly positive answers. However, I’m not sure that this means that Albania is actually known on the other side of the world for its beaches because in my experience they are the type of people that enthusiastically comment on just about any topic.

I think most travellers have excessively big backpacks.

Backpackers

The nicest beaches are a bit out of town. This is what the Aussies were talking about.

Clear blue water

The climb is tough though.

But totally worth it.

Finally

Beer

Climbing back was easier since I’d had a beer.

Hold onto the ropes

The prices in the city are noticeably higher than in Tirana or Vlora. By the way, there is no need to exchange euros for leks in Albania at all: they are both used. The conversion rate of 1 euro to 100 lek makes it convenient, but it’s still harder to count money as there are two types of coins and banknotes.

Some buildings in Himarë are old and abandonded, most are unremarkable.

Abandoned buildings

However, up on the hill there’s Himarë Fshat: the old town, which was once built and inhabited by the Greeks (just like new Himarë).

Streets of the old town

View from the hill

The castle dates back to 5-4th century BC.

Himarë Castle

What I really liked was the old church, built in about the 10-11th century. There was no one there, it was quiet and refreshingly cool inside, which relieved me from the heat that tormented me while climbing up. It was a spiritual experience.

St. Sergius and St. Bacchus Church

On my second night in Himarë, as if someone instructed me, I entered a bunker at dusk. I don’t remember anything I saw there, but I recall the wind, the echoes of dripping water, the creaking of rusty gates and many other sounds that I have no simple description for. I also remember the excitment of once again hearing the chirping of cicadas against the gentle rhythm of the sea upon exiting.

Bunker

Tunnel

Dhërmi

The next morning I had to decide where to travel next and I figured that I should head East, since I eventually had a flight from Sofia. So I chose to go to Berat. Due to the nature of hitchhiking, I visited a lovely place that wasn’t explicitly present in my fairly vague plans: Dhërmi, where I was dropped off after a ride with Albanian Greeks, who were listening to Italian radio.

Dhërmi

There are Orthodox road shrines, just like in Greece.

Road shrine

Once again, in order to reach the interesting places I had to climb up in the heat.

Stairs

View from the top

Church of St. Spyridon

Up on top of the hill there’s the Monastery of St. Mary. Another spiritual experience.

Monastery of St. Mary

Exploring a Greek region of Albania with Christian Orthodox churches was a pleasant surprise to me. Looking back, this was the part of Albania I enjoyed the most. But there are tensions. I noticed it while reading the translated Albanian Wikipedia. For example, the page on Himarë says:

At the end of the Second World War, a Greek minority is present in Himara, who, for extremist political purposes, says that Himara is now a Greek city, which causes problems with the Albanian community that has hosted them for more than 50 years in Himara. But in fact, the policy for the Greekization of Himara dates back to shortly before the declaration of Albania’s independence, where the powerful clans of the Greek Megaliidhesa and especially the Greek Orthodox Church, carrying out the policy of many Greek governments, have dictated with various elements such as Spiro Milo and others in the following, since 1912 until today with the idea that Himara is a Greek minority. But historically the Himariots have not supported this policy and for decades fought with paid extremist circles, never to realize the Greek dream for the Greekization of the Himariot population.

And on Dhërmi:

Greek is a local language, created by the inhabitants of the area as a means of communication in commercial treaties and similar to the archaic versions of today’s Greek. There are several hypotheses about this. One of them, but not proven, could be that the inhabitants of these three villages are of “Greek” origin. The other hypothesis, and the most acceptable, is the use of the Greek language, which may be a consequence of the accommodation made by the Greek islands during the Turkish attacks, as well as during the needs of trade on the Greek islands, especially Corfu.

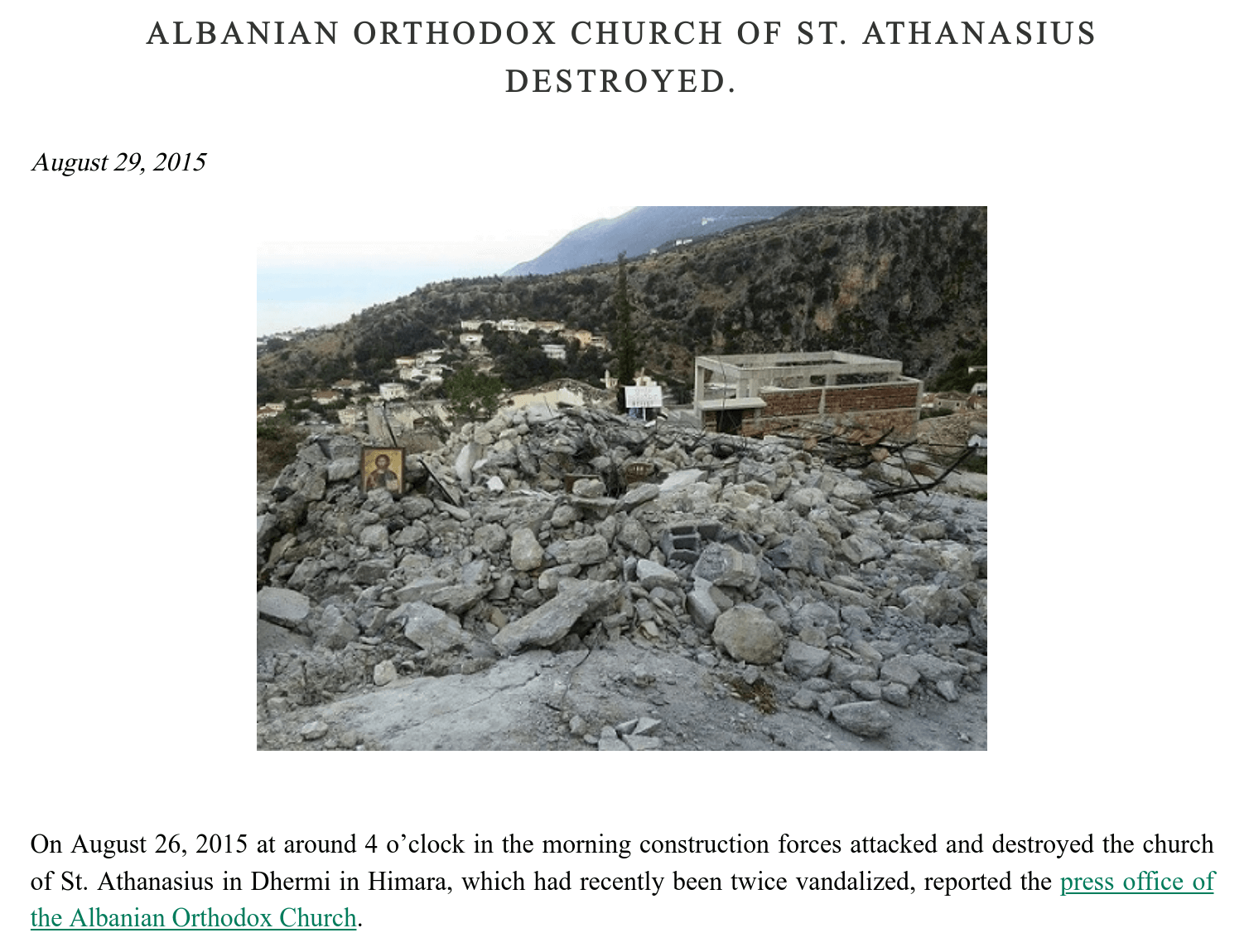

But actions speak louder than words. In 2015 an Orthodox church in Dhërmi was demolished overnight.